The Talimali Band of Apalachee

by Dayna Bowker Lee

The Kisatchie Hills

After being driven from their village by Baldwin and his agents, the majority of Apalachee sought refuge in the Kisatchie hills where they established two small settlements. Jacquite Vallery led the Sang-Pour-Sang village, and his brother, Antoine Vallery, the last traditional chief of the Apalachee, established his settlement on Bayou Cypre (G. Bennett interview, March 10, 1998). Their brother, Jean Baptiste Vallery II, remained with his family and followers near the old Apalachee village site around present-day Colfax where they eventually merged with other multicultural communities.

For the remainder of the 19th century, the Apalachee interacted with local American Indian groups, as well as their métis and Creole neighbors. The also joined with mestizo families once connected to the old Spanish presidio of Los Adaes. The Apalachee were the only known tribal group to inhabit the Kisatchie Hills by the middle 19th century, and were probably the Indians who staged a dance and stickball game at the plantation home of Ambrose Le Comte in 1863 (Bearss 1972:47). Planter families like the LeComte/Hertzogs, LeCourts, and Chopins became patrons and friends of the tribe. After the Civil War, a few Irish Catholics merged with tribal families and became the conduit by which goods like baskets, produce, livestock, and cross-ties for the railroad industry entered the markets of Cloutierville.

Alfred Carnahan house, Sang-Pour-Sang community, Kisatchie Hills. Photograph courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee, tribal archives.

Ernest Brossette, Caddo/French (métis), and Josephine Pattie, Adaesaño (mestizo – descended from the families who once occupied Los Adaes Spanish presidio near present-day Robeline, Louisiana). Photograph courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee, tribal archives.

Francis Kerry and Ezzie Basco. Photograph courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee, tribal archives.

Mary Frances Vallery Kerry, also known as Shalotte, daughter of Apalachee leader, Benoist Vallery. A tall woman with a commanding presence, Shalotte rode a large white horse and oversaw the communal fields. Here she is seen harvesting corn. Photograph courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee, tribal archives.

A close relationship developed between Jacquite Vallery and Dr. Jean Baptiste Chopin, a planter in lower Natchitoches Parish. Chopin, a physician who came from France in the early 19th century, married Creole Julia Benoist, and established a cotton plantation business with her mother, Suzette Rachal Benoist (Mills 1985:532).

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Chopin sent his family to France while he remained on the plantation with a few servants along with Jacquite’s son Benoist Vallery, apparently named for Chopin's wife's family. When Union troops moved through the area and began to seize and burn property, they abandoned the plantation and sought refuge “at Jacquitte's [sic] place in the pine woods” (Rachel Morris deposition, Chopin Collection, October, 1882). Jacquite’s log house still remains standing on family land and is an object of great cultural patrimony to the contemporary tribe.

The cabin of Jacquite Vallery with whom Dr. Chopin and his servants hid during federal raids during the civil War. The additions to the cabin were made later and are used for storage. Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU.

By the middle 19th century, the Apalachee descendants formed three small communities, the original two at Sang-Pour-Sang and Bayou Cypre, as well as a third settlement that grew up around the common agricultural area at Yay-Yay Fields. The villages were connected by footpaths and were located about a mile apart from one another.

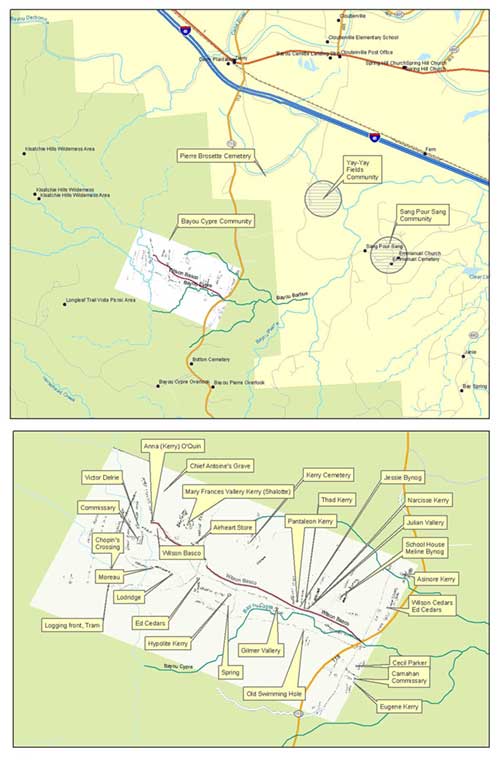

Click map for a larger map. Map delineating the three Apalachee communities in the Kisatchie Hills. The 20th century Bayou Cypre community is detailed below based upon the memories of Jim Kerry and Gilmer Bennett. Map created by Michael Fontenot, LRFP, NSU.

Yay-Yay Fields, site of the former settlement and communal gardens. Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU.

Despite increasingly complex ethnic blending, the three small communities continued to function as Apalachee tribal divisions. Upon the death of a division leader, the office passed to his son or maternal nephew and the community danced all night to honor both the old and new leaders (TK interview, 27 January 1998). These communities remained located on the periphery of white settlements beyond the notice of their Anglo-American neighbors.

The Apalachee continued to practice Catholicism and registered marriages, births, and deaths at the Riviére aux Cannes chapel, later St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in lower Natchitoches Parish. Weekly services were often conducted in people's homes. The children do not appear to have attended school until around the turn of the century, when community schools were established. Although unable to read or write, Meline Bynog instructed the children of Bayou Cypre in church history and Catholic catechism (GB interview, 10 March 1998).

Meline Bynog who ran

the Bayou Cypre school.

Photograph courtesy of the

Talimali Band of Apalachee,

tribal archives.

Living tribal descendants cannot pinpoint exactly when their Anglo-American neighbors began to once again encroach on tribal territory. As had been the case with their Red River village site, aggressions against the Apalachee were carried out by those who coveted their lands Although the bottoms and the hills were neither valuable nor particularly desirable in the early 1800s when land was plentiful, by the 1880s these areas rich in natural resources became more attractive. Railroads and lumber companies began to buy up property or take long-term leases in the area during this time; numerous patents for lands around and in the Bayou Cypre community were issued to the New Orleans Pacific Railway (Federal Tract Book 39:40) in the 1870s and 1880s

Traditional history recounts that federal agents arrived in the Bayou Cypre community about 1901 and relocated some of the Apalachee to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) (GB interview, 10 March 1998). This “second Indian removal” occurred in small southern tribal communities at this time as agents and land speculators tried to sever remaining tribal ties to valuable tracts of land. Many southeastern Indians were persuaded to relocate with the promise of land allotments, most of which never materialized. Linguist Albert Gatschet found three families of Apalachee living alongside Creek families in Indian Territory by the beginning of the 20th century (Swanton 1946:91).

Relocation of some tribal members did not ease the growing problems for the Apalachee communities. Anglo-American marauders, called “White Hats,” began increasingly violent raids into the Yay-Yay Fields community by 1908 in an attempt to force the Indians from their homes. They rode down women in the fields, shot through house windows, and even killed a child (TK interview, 27 January 1998). The intensity of the raids escalated between 1913 and 1915 (GB interview, 10 March 1998).

They really started in hard on them.…And they got to where they were shooting the women because…there were more women than men. They shot Marceline, my aunt, they caught her hoeing cotton in the field. They chased Grandpa [Amos Bennett] down with the horses and dogs, hit him in the head with something and busted his brains out. Oscar Vallery was holding him, his half-brother, when he died.

These raids are confirmed by non-Indians who lived alongside the Apalachee in the Kisatchie hills (Bacle in Kadlecek and Bullard 1994:494).

Along about 1910 or 1912 the people in the Kisatchie area didn't like the Indians. They were trying to get them out…so they used dogs and they'd chase them. There were only about 25 or 30 of them left in here.…Some of them never did leave but they didn't have a house. For years they just lived in the woods. They'd peel the bark off some cypress trees and stand it up on some poles and that's where they'd winter.

In an effort to elude their tormentors, many survivors built up small mounds in Sang-Pour-Sang Lake, using earth they carried out into the water in sacks. They built bark lean-tos on the mounds and hid from the raiders (TK interview, 27 January 1998).

About 1915, shortly after the depredations began, community leader Oscar Vallery decided it was time to abandon Yay-Yay Fields. Only three or four families left at first; but when the problems continued, it was decided to abandon the settlement altogether. “In 1919, they got them all together, some of them from over at Sang-Pour-Sang and some from over on the bayou, and they all left there at night; they got on the train and left” (GB interview, 10 March 1998). The exodus was quietly planned and well-organized. Before boarding the train at Lena, those who would leave the only home they had ever known stopped by a family home in Bayou Cypre to share a final meal together. “I recall that everybody kept it very quiet. Those that stayed moved out on the bayou . . . further out in the woods” (EH interview, 21 March 1998).

Emmanuel Catholic Church, ca. 1970, from the George Stokes Collection, Cammie Henry Research Center, Northwestern State University.

Oscar Vallery remained a tribal division leader in Monroe. Dennie Vallery led the Sang-Pour-Sang community, and Gilmer "Boy" Vallery, the son of Benoist Vallery, led the Bayou Cypre community, and relations remained close between the divisions. Two or three times a year, Oscar Vallery traveled back to Bayou Cypre to participate in arbor meetings where the problems and issues of the larger community were addressed and spiritual needs fulfilled (EH interview, 21 March 1998).

Emmanuel School, ca. 1910. Left to right, front: Ranie Basco, Lula Vercher, Eliza Delacerda, Herbert Basco, Marie Bynog, Margaret Bynog, Lizzie Carnahan, Mitchel Carnahan, Wesley Vercher, Henry Bynog, Luma Vallery, Adam Carnahan, Ambrose Delacerda, Sam Gorum, Gilmer Delacerda, Louis Gorum, Emmit Watson, Lema Delacerda, Raul Bynog, Bennie Delacerda.

Second row: Sylvia Basco, Catherine Delacerda, Marie Walker, Freddie Delacerda, Clyde Basco, Fred Carnahan, Jimmie Delacerda, Terrance Vercher. Third Row: Mary Ellen Vallery, Mary Alice Basco (infant), Alexander Basco, Sr., Alexander Basco, Jr. (infant), James (Jim) Delacerda, and Ebbie Hargis (teacher). Photograph courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee, tribal archives.

The Emmanuel Catholic Church and school were established near Sang-Pour-Sang after 1900 to serve the Apalachee and the mixed French and Spanish Catholic families who inhabited the hills. The Bayou Cypre community was sometimes cut off from the church by high water, so services were held in the homes of Hypolite Kerry or Gilmer Vallery (EC interview, 27 January 1998; GB interview, 10 March 1998; Queen of the Rosary 1:76).

In the 1930s, these remote communities came to the attention of Fathers G. M. Scanlon and George Carpentier of the Dominican Order located in Alexandria, Louisiana. The two priests established and maintained the Boyce missions, which included churches at Gorum, Marco, Monette's Ferry, Emmanuel, and Flatwoods, with smaller stations at communities like Bayou Cypre (Queen of the Rosary 1:76). About this time, the Dominican Sisters took over the school at Emmanuel. Bayou Cypre, which had been without a school since around 1919, began to receive educational assistance from the church as well (Queen of the Rosary 2:53).

Soon after the establishment of the Gorum Mission search for the isolated people in the wooded hills and on the winding bayous began.…Father Carpentier followed the many crossroads and came upon several huts and houses here and there tucked away.…The inhabitants called this solitary settlement Bayou Cypre.…Because of the remoteness of these people of Bayou Cypre from a steady human contact – their educational standing left much to be desired. Father Carpentier made his regular trips from Boyce, brought young and old alike all sorts of books, and the school sessions started. Interest in something else besides physical work took root and soon the confidence towards the missionaries was won.

Stations of the cross altar alongside the

Emmanuel Catholic Cemetery,

Sang-Pour-Sang Hill, Kisatchie Hills.

Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU.

Although the fathers assumed that the Bayou Cypre community had been without formal religious instruction, members of the community attended services at Emmanuel Church whenever possible and many were buried at the Emmanuel cemetery, previously called Sang-Pour-Sang Cemetery. The church and cemetery remain central to the contemporary community (Carnahan, et al. 1985:11-15; GB interview, 10 March 1998).

Looking out over Kisatchie forest and hills from Emmanuel Catholic Cemetery, Sang-Pour-Sang Hill, Kisatchie Hills. Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU.

The Apalachee consolidated into two communities at Sang-Pour-Sang and Bayou Cypre in the years following the departure of Oscar Vallery and his people. Fourteen families were counted in Bayou Cypre in 1943 (Queen of the Rosary 1943 2:53). Persecution of community members by outsiders continued sporadically. “They never did leave them completely alone, even on Bayou Cypre. . . . The ones that stayed there had a lot of guts” (GB interview, 10 March 1998).

Left to right: Julie, Frances, Virginia,

and Albert Vallery ca. 1920 standing

in front of the cabin built by Benoist Vallery.

This cabin was burned while

Gilmer “Boy” Vallery slept inside in an

attempt to drive the Apalachee out

of the Bayou Cypre area.

by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU.

After World War II, Apalachee land once again became the object of desire for their neighbors. In 1951, when the United States was in the process of acquiring property to add to Kisatchie Forest, the house of community leader Gilmer “Boy” Vallery, built over a century earlier by Benoist Vallery, was torched with Vallery still sleeping inside (GB interview, 10 March 1998).

His nephews drug him out of the house still alive. They knew the men that done it. They watched them set it on fire. [Vallery] went over to his son-in-law’s. Uncle Thad had left out of [Bayou Cypre] before that because he was having trouble with them in there, so he had moved in the 1920s.…So when Grandpa, whenever his house burned, he went to Uncle Thad and he stayed there just a while, then he went up to Monroe to see Oscar, then he went to see his daughters, and then he died there before he got back home.

Along with the house, a violin given to Benoist Vallery by Jean Baptiste Chopin, family heirlooms, and all paper records belonging to the Vallerys were destroyed. After Gilmer Vallery was buried at Gorum, the remaining Apalachee descendants abandoned Bayou Cypre altogether. Today within the remote reaches of Kisatchie National Forest, the site of the old Vallery homeplace, can still be identified by the ornamental, medicinal, and fruited plants – for example, crepe myrtles, wax myrtles, huckleberries – still found growing there.

Left to right: Julian, Hertzog, Melissa, Virginia, and Frances Vallery, ca. 1915. Julian Vallery is holding the violin given to his grandfather by Dr. J. B. Chopin. Frances Vallery was the mother of the current tribal chief Gilmer Vallery. Photograph courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee, tribal archives.

Tribal Chief Gilmer Bennett at the swimming hole near his grandfather's house. Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU, 2005.

Looking into the copse of trees surrounding the Bayou Cypre site of the house built by Benoist Vallery, burned in the 1950s. Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee, LRFP, NSU, 2005.

Tribal Chief Gilmer Bennett

at the Brosette Cemetery

beside the headstone of his

grandmother, Mary Ann Bennett.

Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee,

LRFP, NSU, 2005.

Huckleberries growing at the site

of the Vallery house.

Photograph by Dayna Bowker Lee,

LRFP, NSU, 2005.

Years of persecution made the Apalachee wary in their dealings with outsiders. Rather than claiming tribal heritage on legal documents and in public, children were forbidden to talk about their ethnicity and were instructed never to ask about “the land” or the lawsuit once filed against the government. Paper records were periodically destroyed and increasingly in civil and church records, members self-identified as white when they were counted at all.

Before his death in 1956, Oscar Vallery instructed his son to burn all his possessions. “Whenever he died, his son took his kids over there and they built a big fire. He had books and papers, he even had his old Civil War uniforms. He didn’t want . . . people to know who they were” (GB interview, 10 March 1998). The tradition of burning important paper records was a common response to the persecution the Apalachee had endured. When asked if she had documents which might substantiate her heritage, Oscar Vallery’s granddaughter stated, “I burnt everything me and my daddy had. I burnt them when my children were all very young so no one could see them” (EH interview, 21 March 1998). Oscar Vallery was buried near Bayou Camite in the Brossette Cemetery belonging to his wife’s family.

The Apalachee before 1763 | The Apalachee Village, Rapides Parish | The Kisatchie Hills | Epilogue | Appendices