The Talimali Band of Apalachee

by Dayna Bowker Lee

The Apalachee Village, Rapides Parish

Among the first of the "Petites Nations" to petition the French government for permission to relocate to Louisiana, a delegation of Apalachee visited new Orleans in 1763, prior to the transfer of the colony to Spain. The French provided them with boats and guides to take them to new lands on Red River in present-day Rapides Parish, about halfway between the Natchitoches post and the confluence of the Red and Mississippi Rivers (Hunter 1994:4-5). There they built homes atop a bluff overlooking Red River on some of the most spectacular and fertile real estate in the region.

Location of Rapides village site on the bluff overlooking Red River. The village site was identified and explored archaeologically by Donald G. Hunter, Coastal Environments, Inc. (1985, 1994). Photograph courtesy of Donald G. Hunter.

The Apalachee established a village and fields, living quietly and autonomously until 1767, when Etienne Layssard arrived to serve as commandant of the district. The Apalachee did not welcome the Spanish administrator. After all, they had turned away from the Spanish and toward the French in the early years of the 18th century.

The tribe was quick to assert its independence from the new regime and continued to act as a sovereign nation. Shortly after Layssard’s arrival, the Apalachee helped a group of Alabama clear a place on which to settle near their village. The land claimed by the Apalachee was also claimed by Mr. Vincent, a local French Creole who lodged a complaint with Commandant Layssard about what he perceived as encroachment. Layssard recommended that Vincent continue to use the land until the governor could be consulted to settle the dispute. A few mornings later, the entire Apalachee community arrived at the commandant’s habitation and began to fell trees and clear land. When Layssard protested, tribal chief Martin informed him that since Vincent was allowed to use their land, they would take some of the commandant’s in return (Hunter 1994:5).

The Parish of St. Luis des Appalages was established at the Apalachee village in 1764 (Hunter 1994:6). Itinerant priests who traveled from the Rapides post to Natchitoches served the tribe, drawn there by the massive wooden cross that dominated the hilltop village. Still devoted Catholics, the Apalachee nation was the only tribal entity on Red River known to have had its own parish. Father Isidro Quintero counted 135 Apalachee and Taensa in 1796 settled together in the village above the rapids (Notre Dame Archives Calendar, 21 November 1796).

For the remainder of the 18th century, the Apalachee and other small nations lived unmolested, surrounded by French Creole families with whom they formed close relationships. The purchase of Louisiana by the United States in 1803 would forever alter tribal ways of life for the Apalachee and other southeastern Indians. The previous year, a group claiming to be Taensa and Apalachee informed Commandant Layssard that they had sold their communal Red River lands to American merchants Alexander Fulton and William Miller to satisfy a $2,600 debt and to acquire additional merchandise. Representing the Apalachee was Louis, chief of the Taensa whose wife was Apalachee, and who had settled with the Apalachee on Red River by 1788. The recognized traditional Apalachee leader, Etienne, was residing at that time in the northern Apalachee village near present-day Shreveport and was not present to represent the interests of his people (Hunter 1994:18).

This spurious sale began a legal battle that would wage on for decades. The 1806 Nicolas King map, created from information collected by Peter Custis and Thomas Freeman on their expedition to explore the Red River, shows the Apalachee (“Indian Settlement”) on the west side of Red River below the Pascagoula village (“Indian Village”).

Click for larger map. Above is detail from Map of the Red River in Louisiana from the Spanish camp where the exploring party of the U.S. was met by the Spanish troops to where it enters the Mississippi, reduced from the protracted courses and corrected to the latitude, 1806. Nicholas King, based upon observations from the Freeman and Custis expedition. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. DIGITAL ID g3992r ct000689 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3992r.ct000689

On June 14, 1814, the Apalachee filed a formal complaint with the U.S. Land Office in Opelousas charging that Miller and Fulton had never paid the tribe for the lands they had supposedly purchased. The Apalachee further denied having been indebted to the merchants in the first place. Indian agent Dr. John Sibley supported the Apalachee cause, writing the U. S. land commissioners (January 20, 1814, ASP, PL, 1834, III:218) to refute the purported debt and sale of land to the merchants. Unfortunately for the tribes under his authority, Sibley was replaced as Indian agent shortly thereafter, due in part to his attempts to protect the rights of the Indian groups within his agency. At this time, the Apalachee village contained about 25 families who divided their time between hunting and agriculture (ASP, PL III, 1834:218).

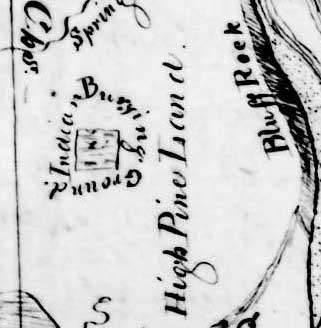

The land commissioners did recognize a problem with the Miller and Fulton transaction and recommended in 1813 that title be confirmed to the merchants for the Taensa land only (ASP, PL II, 1834:796). Instead of awarding title to the Apalachee village site collectively to the tribe, however, the commissioners auctioned off the remainder of the tract as public land. It was purchased by Isaac Baldwin, who also purchased the Fulton and Miller claim. Baldwin established his plantation just below the Apalachee village and immediately began efforts to evict the disenfranchised Indians from their homes (Hunter 1985:26). Approximately 150 Apalachee and Taensa still occupied the Red River village at that time. Kenneth McCrummen who surveyed the land in 1819, located the “Indian burying ground” on the west side of the river near the village site. The Indians occupied both sides of the river, including the large point south and east of the burial ground on which McCrummen notes “Indians hold this part.”

Click for larger map. Detail from 1819 survey of the Fuller and Fulton Claim by Kenneth McCrummen, National Archives, Washington, D.C., Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1880. (Courtesy Donald G. Hunter)

From this point forward, the Apalachee would suffer intense persecution at the hands of the ever-increasing numbers of Anglo-American immigrants. To escape annihilation, the remaining tribal families sought refuge in marginalized ecological and occupational safe zones in the Kisatchie Hills of Natchitoches Parish. The dispute over the village lands continued for several years, and in 1832, Indian Agent Jehiel Brooks recommended that title to the Apalachee lands undergo legal investigation and that the sale to Baldwin be canceled (Hunter 1985:28). Baldwin, however, persisted in his attempts to evict the Indians, boasting in 1826 that he had been able to evict all but five or six families. Indian agent George Gray stated in 1827 that depredations by Baldwin had driven at least ten families of Apalachee and Taensa into Texas (Hunter 1994:29-31).

Patents to part of the disputed tract had still not been issued by 1832, but the Apalachee had abandoned their village site by the time they petitioned the U. S. Senate and House of Representatives for reparations in 1834 (Bailey 1834).

[T]he Apelatch Nation of Indians Residing in the State of Louisiana and parish of Rapides on the left Bank of Red River most Respectfully States, that they have inhabited the above-named place for the last 80 or 90 years[,] that we had made considerable Improvements in Bilding [sic] our Village besides Improving and cultivating the lands, that some time in the year of 1830 our lands was offered for sale at the land office . . . when one Isaac Baldwin became the purchaser of all our Village together with the land, shortly after which time our village was burnt, our farm lands wasted, and our women and children driven from our lands by the said Baldwin.

The last official census of the tribe made by Agent George Gray in 1825 counted 20 men and 25 women (Hunter 1994:30). Ownership of the Apalachee village site remained in dispute for years to come. Although part of the land was eventually awarded to an Apalachee descendent in 1853, her Anglo-American husband actually received patent to the land (Benguerel and Posey, March 18, 1857, GLO). The Apalachee then living in the Kisatchie Hills never learned of the final disposition of their tribal territory.

The Apalachee before 1763 | The Apalachee Village, Rapides Parish | The Kisatchie Hills | Epilogue | Appendices